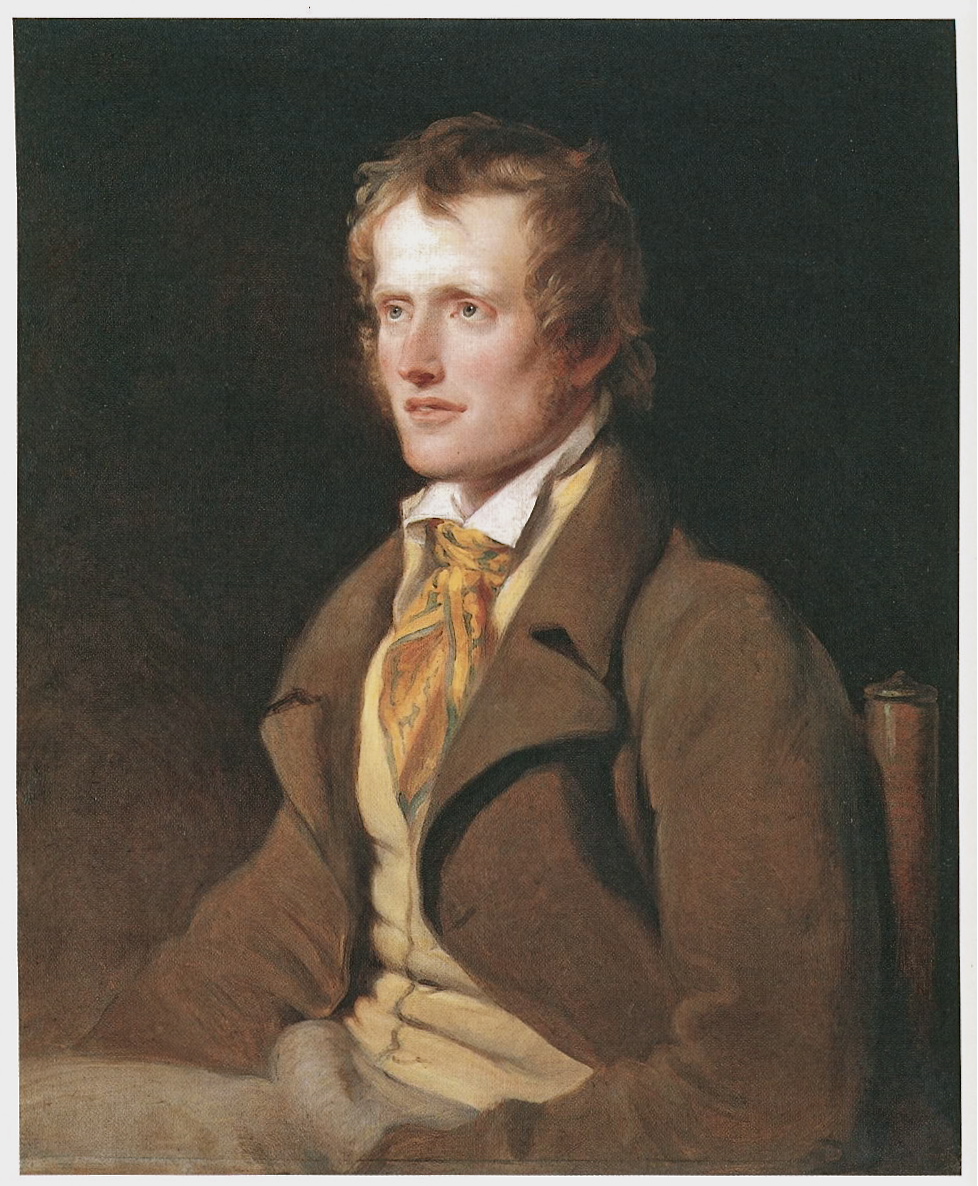

Nineteenth-century poet John Clare wove together “descriptions of the environment and accounts of human life,” making no distinction between human and natural history. The anthropologists Richard D.G. Irvine and Mina Gorji argue that this makes him in some ways a poet of our current age, the Anthropocene. He drew connections between the reduction of insect life and the corresponding diminishment of the birds and mammals further up the food chain, essentially foretelling the dire environmental state we see today. Clare recognized an inherent value in land unconnected to human use. In this he predates Aldo Leopold’s land ethic by more than a century. Against the “progressive” ethos of “improving” land for private profit, Clare recognized how ecologically important habitat like wetlands were. He mourned the moles being hung (yes, hung) by farmers as pests, noting their vital role in turning the earth, and, coincidently, churning up ancient Roman artifacts. In addition to standing up for the moles, Clare had a fondness for weeds, which are, after all, just plants that aren’t wanted in a particular place. They appear to lack a use value, but that concept is anthropocentric. Irvine and Gorji value these alternatives to anthropomorphism. They conclude, “from an non-anthropocentric perspective, looking at our actions with the recognition that we are geological agents, we might be startled to learn that we are the weeds.”

Source: JSTOR Daily, 4 May 2018

https://daily.jstor.org/what-this-19th-century-poet-knew-about-the-futu…

- Login om te reageren