In her recent Environmental Protection Report entitled Small Steps Forward, the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, Dianne Saxe, called upon the government to put words into action to monitor biodiversity, combat wildlife declines, control invasive species, and follow through on better forest fire management. The large-scale loss of biodiversity is a crisis in Ontario and around the world. Ontario's most "at risk" species are snakes, turtles and freshwater mussels. However, many freshwater fishes, birds and mammals are also experiencing alarming declines. In addition, when you include species that may be at risk, we also find mosses, amphibians, lichens and many vascular plants. Overall, about 30 per cent of all species groups in the province are either sensitive, maybe at risk or already at risk. This year's report highlights examples of current wildlife declines in Ontario.

Bats

Eight species of bats are native to Ontario. Five of these species hibernate in caves or abandoned mines, which makes them susceptible to white-nose syndrome, an aggressive fungal disease. Four of these "cave bats" - eastern small-footed myotis, northern myotis, little brown myotis (bat) and tri-colored bat - have been classified as endangered due to the disease. The big brown bat is thought to be less affected by WNS. Three other species, known collectively as "tree bats", migrate south each winter and do not use caves or abandoned mines. Their susceptibility to WNS is unknown.

Before WNS, the little brown myotis was the most common bat species in Ontario. Now, all known little brown hibernation sites are affected by WNS, including sites in the Bancroft area. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forests (MNRF) has little hope that the species can recover in Ontario. Because of their classification as endangered, these bats are protected from being killed, harmed or harassed, and from having their habitats damaged or destroyed. It also means that recovery strategies must be prepared for these species.

Currently, there is no treatment for WNS. There is, however, promising research that is being done. In research done at Georgia State University, some bats were able to survive WNS infection through exposure to a common soil bacterium, which produces compounds that inhibit the growth of the fungus. There also appear to be some small populations that are surviving, even in areas affected by WNS. However, it may be too late for Ontario's cave bats, which have already experienced massive die-offs.

In 2015, Ontario released a White Nose Syndrome Response Plan. It outlines a co-ordinated provincial response with respect to prevention, monitoring and research. Among the plan's goals are to increase public awareness about WNS and to limit the inadvertent spread of the disease by human activities. The fungus can be spread by people who visit caves and abandoned mines. MNRF's current research initiatives include developing a citizen science network to contribute to monitoring and identifying natural caves/hibernacula and maternity roosts as well as monitoring known maternity colonies and hibernacula at appropriate times of the year.

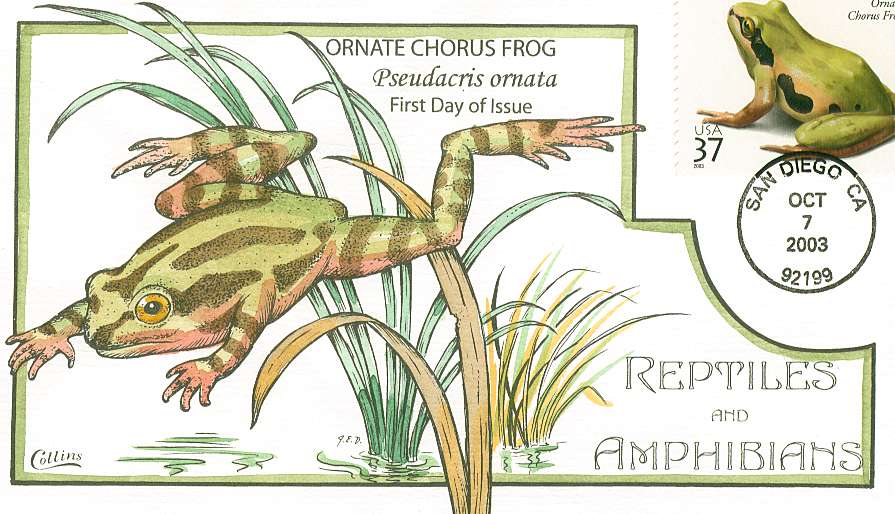

Amphibians

Amphibians are the most threatened group of vertebrate animals in the world, with 42 per cent of amphibian species in decline. Ontario's amphibians are faring only slightly better. Of the 27 native species and subspecies of frogs, toads, salamanders, and newts, three are believed to be extirpated (meaning that they no longer live in the wild in Ontario), and an additional five species are listed as endangered. Over the last several decades, researchers have also observed declines (some localized) in several Ontario species, including the pickerel frog, bullfrog and western chorus frog. Fortunately, these species still seem to be doing well in the Kawarthas.

One of the major drivers of the international amphibian decline is a chytrid fungal infection that has caused mass mortality of frogs, toads and salamanders. This fungus has not been a major threat to Ontario's amphibians to date, though there are concerns about their potential vulnerability. In Ontario, the most significant threats are habitat loss, habitat degradation (e.g., from pollutants such as agrochemicals and road salt), habitat fragmentation, road mortality, overharvesting, invasive species, and climate change,

Large areas of amphibian habitat, particularly woodlands and wetlands, have been destroyed or degraded by development, infrastructure, roads, forestry, aggregate extraction and mine development. There are various provincial policies that are supposed to provide a degree of protection for wetlands; however, these crucial habitats continue to decline. For example, provincially significant wetlands are not protected from agricultural drainage under the Drainage Act.

Source: The Peterborough Examiner, November 17, 2016

http://www.thepeterboroughexaminer.com/2016/11/17/our-biodiversity-is-a…

- Login om te reageren