To many people bugs are pests but in reality out of the millions of species worldwide only a tiny handful are actually true pests. The other, harsh, reality is that overall there definitely aren't as many species or numbers of bugs around as there were in the past. Why should that be important and why should we care - after all, insects are pests?

Well for one, many of the birds species we all know and love are declining because of either secondary pesticide poisoning or the lack of insect food available, especially at breeding time. Let's face it; every time we see a bug we don't want, we reach for the spray. Transfer that to an agricultural scale and you get mass extinction on the scale of the dinosaurs, but because many are tiny little inconspicuous creatures that we rarely see, we don't notice or care.

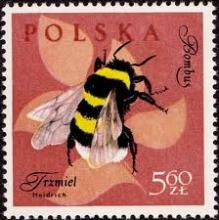

This is a fact: three of the 25 British species of bumblebees are already extinct and half of the remainder have shown serious declines, often up to 70%, since around the 1970s. In addition, around 75% of all butterfly species in the UK have been shown to be in decline. Insects of all sorts play a massive role in our lives and indeed our survival yet we disregard them so easily.