British countryside birds take a tumble

- Lees meer over British countryside birds take a tumble

- Login om te reageren

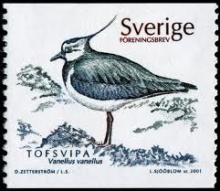

The latest figures from the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) show that four breeding wading birds have reached their lowest levels since the survey started in the early 1990s. Volunteer birdwatchers reported particularly low numbers of lapwing, oystercatcher, snipe and curlew during the spring of 2011. These birds breed on wet grassland and upland habitats across the UK, where they rely on earthworms and other invertebrates for food. All four species saw sharp declines between 2010 and 2011, of 19 per cent for oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus, 18 per cent for lapwing Vanellus vanellus, 40 per cent for snipe Gallinago gallinago and 13 per cent for curlew Numenius arquata. The BBS produces annual population trends for over one hundred widespread bird species. Ten species have declined by more than 50 per cent since the start of the survey in 1994, including turtle dove, which has declined by a staggering 80 per cent. Since the start of the survey Britain has lost more than half of the following ten species: Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur -80%; Willow Tit Parus montanus -79%; Wood Warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix -65%; Whinchat Saxicola rubetra -57%; Grey Partridge Perdix perdix -55%; Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos -52%; Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava -50%; Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca -50%; Spotted Flycatcher Muscicapa striata -50%; Starling Sturnus vulgaris -50%.