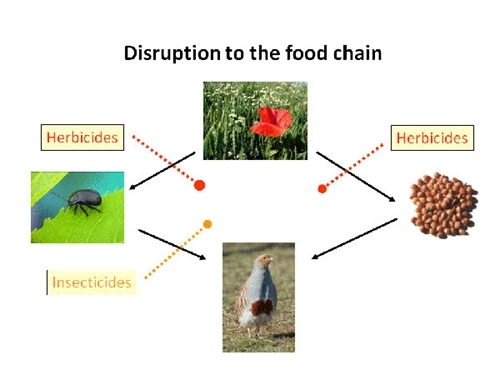

Farmland is home to hundreds of plant and thousands of animal species, many of which are highly dependent on each other forming a complex food web. This was first revealed by our early work on the grey partridge in Sussex. The population of grey partridge was partially dependent on the survival rate of the chicks, which in turn depended on them sourcing enough protein-rich insects. The insects that were most important to the chicks were largely weed-feeding species, and as a consequence, insect abundance was controlled by the management of the crop, but especially by the levels of herbicide inputs. Thus, herbicides were identified as causing an indirect effect on the number of insects within the crop, but also ultimately on the population of grey partridge. Herbicides also reduce the abundance of vegetation and weed seed that are important food sources for insects, birds and small mammals. The indirect effects of pesticides are now a recognised phenomena and along with direct effects are considered responsible for the decline of many other farmland birds because all of them, with the exception of pigeons and doves, feed their young insects during the first few weeks. Autoecological studies have helped to identify the causes behind the decline of some farmland bird species, such as those conducted on grey partridge, corn bunting and yellowhammer. These revealed a strong relationship between invertebrate food availability during breeding and breeding success and this was consequently linked to population change. The majority of other farmland birds also feed their chicks invertebrates because they provide the necessary protein for growth and the energy to resist chilling.

Source: Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust

http://www.gwct.org.uk/research/habitats/farmland/farmland-food-webs/

- Log in to post comments